Access security

for industrial infrastructures

When the term “access control” is used in the industrial sector, the first thing that comes to mind is securing access to sites, buildings, and factories. Industry has a “physical” security culture. From the moment you enter the perimeter of a site, building or factory, you are authorized to perform certain actions, because you are in a protected area. This is physical perimeter security: the security perimeter is the controlled space you are in. The same approach can be found on the IT side, with a network-based approach to security perimeters: once you’ve entered a network, you’re authorized to perform a certain number of actions on the network’s resources.

With digital transformation, industrial environments are increasingly complemented by IT environments. And we can truly speak of a culture clash: the highly physical culture of industry is confronted with the logical culture of IT. What about access to industrial control system applications by operators who need to manage them (update and configure applications, etc.) on the one hand, and use them on the other? In some factories, aren’t there still shared workstations with shared sessions, that can be used by the industrial operators in that area of the factory? How do we know which operator worked on which equipment? How can we ensure “accountability”? i.e. the ability to determine “who did what, when, and on which equipment”? Can we impose authentication to the plant’s industrial employees every time they use these applications, with sophisticated password policies that sometimes lead to unsecure behavior to facilitate productivity?

We can also understand this different mindset by looking at the nature of the industrial infrastructures used in these plants. In general, there is a large number of equipment and control systems from different manufacturers, and therefore a high degree of heterogeneity in this infrastructure, with technologies that are often specific to each manufacturer. That’s not like an IT infrastructure, where you can find different machines, but with much less diversity and standards: when we talk about administering an IT infrastructure, aren’t we talking about RDP access for Windows and SSH access for Linux, and a few other standards? Isn’t it easier to attack a single standard found in all information systems than a manufacturer’s proprietary technology deployed on a more limited basis? In general, “proprietary” means and implies “secure”, or at least less vulnerable, since fewer players are interested in it (from a security point of view).

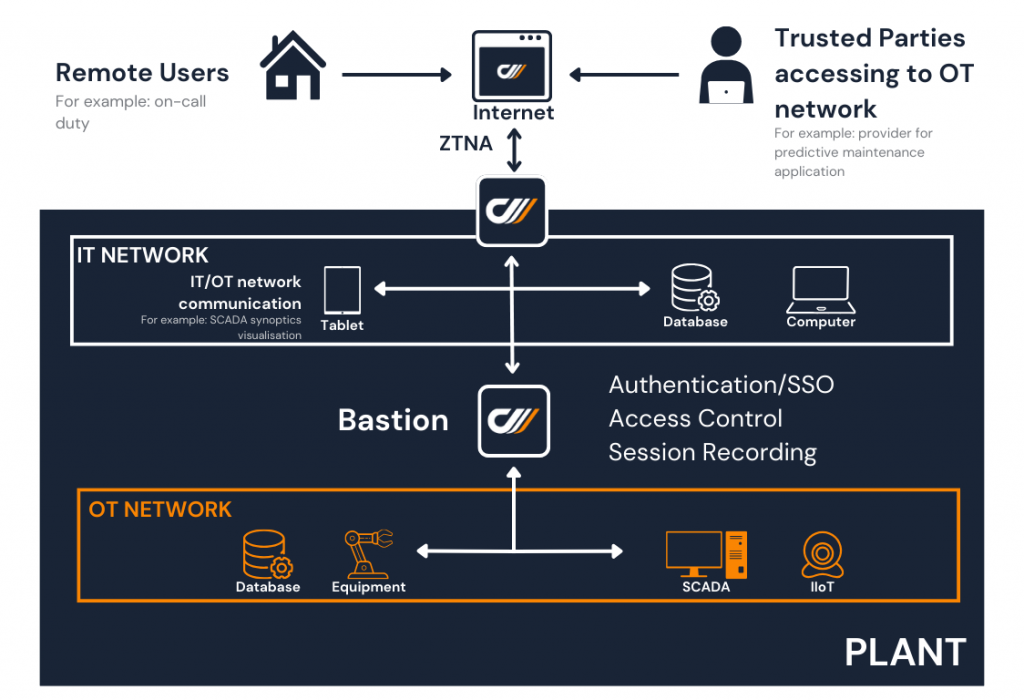

Finally, industrial control systems have generally been, and often still are, accessed exclusively from the plant’s internal network: this is also due to the nature of the protocols and networks used to drive machines and PLCs. We’re far away from the Internet, “the same network for everyone”! However, with the development of ecosystems (manufacturers, service providers), with the consequences of crises such as Covid, which have forced teleworking where possible, with the development of the processing power of the cloud for the analysis of industrial data and the application of AI algorithms, and no doubt for other reasons, factories are opening up more and more. And remote access to industrial infrastructures is becoming a real issue.

In this context, even though IT and OT cultures and environments are very different, IT experience in securing access – beyond physical access control – can provide useful solutions. The heterogeneity of industrial solutions from different manufacturers is a real problem for efficiency and productivity: each manufacturer has its own authentication mode, which can be strengthened; its own way of tracing and logging events on its system, and its own format for logging events. Identity and Access Management (IAM) and Privileged Access Management (PAM) solutions, which are widely deployed in the IT world, all have their place in the industrial world. What can they offer in this context?

> A single access solution for all use cases, and therefore the same user experience when moving from one industrial manufacturer to another.

> Centralized access: security via a single access that can be “strenghtened” (Multi-Factor Authentication, MFA), an MFA that is identical whatever the system.

> Complete and detailed traceability, common to all manufacturers, so that you know who did what on which equipment/system/application, in the form of audits or video recordings. With separate, individual user accounts.

> Avoid operators using their own passwords to access systems. If they have to remember all the passwords for all the applications, with different password policies from one manufacturer to another, they end up writing them down. This is where shared accounts come in.

> The guarantee of regular password changes on industrial systems, without the need for human intervention.

Industrial control system applications are often quite heavy and hosted on a dedicated workstation (by manufacturer, for example). The protocols between these applications and the equipment are standard industrial protocols, but not traditional in the IT world: IT PAM solutions do not natively manage sessions in these industrial protocols. The use of PAM in industry does not necessarily mean providing direct access to PLCs or equipment via these industrial protocols: it’s more a matter of tracking the use of these applications in industrial control systems.

Here are some use cases.

A first example is to provide operators working on a particular manufacturer’s equipment with access to the engineering workstation hosting that manufacturer’s applications. Through the PAM, everything the operator does is tracked and recorded. In this case, the manufacturer’s application is located on a workstation on the plant’s local industrial network, with the application access network on one side, and the equipment and PLC access network on the other. The entire system (applications and equipment) is located in the company’s plant datacenter.

But sometimes the company needs to provide “remote” access to its industrial infrastructure, to its own employees, or to service providers, sometimes starting with the manufacturers of the equipment it has deployed. “Remote” here means from another network, from the workstations of its teleworkers or its ecosystem partners, from their own offices. Instead of having them come in, it can provide them secure remote access. If the company has sufficient licenses to allow third parties to access its industrial applications, it can give them remote privileged access to the workstation hosting the applications concerned via the PAM solution: all the partner’s actions will then be traced and recorded, as in the first example.

However, if the company has not provided a user license for this scenario, or if it prefers that the partner use its own applications with its own licenses from its own network, it can ask the partner to go through the PAM so that all its actions can be tracked and recorded. In this case, the industrial applications installed on the partner’s workstation interact remotely with the company’s PLCs, while also being monitored by the PAM solution. The architecture of the solution will differ from one industrial manufacturer to another, some requiring it to be on the same network as the PLCs, others allowing remote access on different networks. This is where the architecture of the PAM solution comes into play: it must allow seamless integration into an industrial network architecture, while securing access to applications and equipment.

Often, local PLC networks are isolated by outgoing network diodes: the solution must therefore be able to operate in these highly secure network environments, applying the principle that access is always from the most secure zone to the least secure. In this case of secure remote access, there are two types of architectures: one (preferred because more secure) is based on an end-to-end “secure tunnel”, from the “output” of the industrial application to the “input” gateway in the industrial network where the PLCs are located, through which the industrial connection protocols to the PLCs and equipment pass; the other is based on a VPN (if possible, a VPN that filters flows at the level of network addresses and server input ports), allowing the industrial application to “see” the PLCs and equipment it controls on the network.

The new generation of solutions make remote access to a system, whether IT, industrial or mixed, much more secure than in the past. They solve the paradox of creating an impenetrable barrier that can only be crossed by those who are authorized to do so, while protecting the assets to which they grant access. And even if 100% security doesn’t exist, the benefits in terms of operational efficiency and productivity exceed the risk of not using them. For example, a remote intervention that unblocks a production line is better than waiting for an on-site intervention, without compromising the security of industrial assets.

Yes, cybersecurity can be a lever for performance.